2015, Ellen Macarthur Foundation

Demystifying Series: Policymaking and a circular economy

CE-Hub, 2022

This paper is part of a series aimed at demystifying and providing context to a circular economy. The series is aimed at an audience of businesspeople, policymakers and others who may already have understanding of circular economy, are interested in implementing it in their field of influence and wish to know more. This Demystifying series addresses the ‘what’ of circular economy, and the upcoming What Works series will address the ‘how’. We recommend reading the introductory ‘Demystifying a circular economy’ paper in advance of this one.

Authors: Lucy Chamberlin & Georgie Hopkins

Reviewed by members of the Knowledge Hub Steering Group: Steve Evans, Simon Brown, Dan Dicker, Ali Moore, Isabelle Erixon, David Greenfield, Katie Lamb, Danielle Purkiss, Fiona Charnley, along with Nicky Cunningham.

Introducing circular economy and the UK policy context

In the UK, policymaking has traditionally been quite a slow process but is now under pressure to become more adaptive, reflective and transformative, particularly in response to ever-changing societies and global uncertainties (e.g. brought about by pandemics, wars, climate change and rapid digitisation). Some areas of responsibility such as education and the environment have been transferred from the UK government to the devolved administrations of the Northern Ireland Assembly, the Scottish Parliament and the National Assembly for Wales[1]. The circular economy is also a devolved responsibility, and for this reason there are different approaches to achieving objectives as well as varying levels of activity across each of the nations. The UK Circular Economy Package (CEP) 2020 outlines a legislative framework for waste reduction, management and recycling that directly relates to many existing policies in place across the four UK nations, including the 25 Year Environment Plan for England, the Environment Strategy for Northern Ireland, Making things Last for Scotland and Beyond Recycling for Wales[2].

The circular economy is seen by the UK government less as an outcome in its own right, and more as a mechanism for delivering the green economy, particularly the Net Zero agenda. Indeed, the recently published UK Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy[3] heavily references the circular economy as a methodology for reducing greenhouse gas emissions through eliminating waste, keeping materials in use and capturing carbon through regenerating and restoring natural systems. Renewable energy and energy efficiency can only address around 55% of these emissions, and thus the circular economy provides another crucial component for tackling emissions from industry, agriculture and land use[4] – as well as addressing other challenges such as resource scarcity, pollution and waste.

Why is policymaking important for a circular economy?

(See the end of this report for a brief overview of policymaking in the UK)

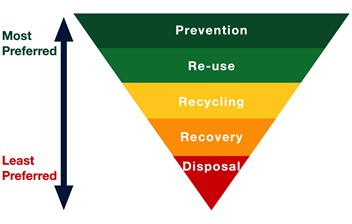

The development of certain policies together with accompanying legislation is an integral element in the UK’s transition towards a circular economy, providing the power and mandate to catalyze transformational change across businesses and society[5]. With policy frameworks initially based around waste and resource use, building on the waste hierarchy and the 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle)[6], policymakers now have a key role in enabling circular economy activities such as repair, remanufacturing and repurposing[7], and supplying the economic incentives required to instigate this. Policy that supports a circular economy needs to address not just waste and resource use, but also infrastructure planning, tax, education and training, skills and employment, environmental and human health, international trade, industry and manufacturing.

Figure 2: the waste hierarchy has mostly focused on products at their end of life, whereas the circular economy takes a more holistic approach

Research shows successful outcomes and greater business investment for regions where policy and legislation are more supportive of circular or sustainable innovation[8]. However, no single policy can achieve this transition, and there is a need for a complementary and interconnected approach across different sectors and industries; a holistic perspective that addresses each stage of a product’s life cycle in a complementary manner will be critical to the implementation of a future UK circular economy.[9]

How does a circular economy challenge traditional policymaking?

By requiring a more holistic view that can enable change at the level of entire systems [10], the circular economy cuts across many traditional silos of activity and poses a challenge to current policymaking practices that usually occur within separate departments. In the UK, while the circular economy is detailed in several strategies, there is no single policy, strategy or plan which underpins the country’s transition and lays out how different sectors and regions should work together. Likewise there is no single government department that has overall responsibility for implementing a circular economy, and thus the different policies introduced risk being too narrow or disjointed and ultimately failing to administer the system-level changes that are needed. Policymaking is often slow to catch up with fast-moving global situations, policies from different departments can unintentionally leave loopholes or miss opportunities, and disparate, ’legacy’ regulatory regimes can unintentionally block new circular practices[11]. One example is certain waste policies which were originally designed to ensure controlled management of waste with minimum negative impacts on health and environment, but which can obstruct the activities of circular economy businesses that want to develop innovative reuse or recycling initiatives from what are currently deemed to be ‘waste’ products.

Given the complexity and number of departments potentially involved in circular economy decision making, the number of actors associated with circular economy policymaking can also prove challenging, both in terms of information dissemination and different interpretations of circular economy principles [see ‘Demystifying the circular economy – an introduction’]. In addition to this, civil servants regularly move roles within the service in order to increase their understanding and reach – but this can also slow down the process of policy creation and prove problematic for circular economy, as each new person needs time to get to grips with its requirements and complexities.

How can policymaking support a future circular economy?

With the increasing demand for scientific evidence to support policy proposals, research highlights the vital role of public organisations, often referred to as ‘boundary agencies’, in supporting the translation of environment and climate evidence into policy[12]. Considering the lack of coherent measurements and metrics for circular economy, and bias that favours the status quo, collaborative and open initiatives such as the UKRI-funded NICER programme[13] can be important vehicles in bridging the gap between science, business, policy and society. As an increasing number of innovative companies move towards circular practices, there are growing opportunities for businesses to engage government bodies and demonstrate where policy and underlying regulation are needed to support the transition, and some are already sharing insights and influencing policymakers[14]. Another important route towards circular economy adoption is through public procurement, which represents around ~16% of GDP in the EU. It is also likely that place-based policy will become more important for instigating action at the local authority or city level, demonstrating the viability and legitimacy of circular economy within society[15].

However, some researchers have noted that issues of equity and inclusion are sometimes overlooked in the rhetoric of a circular economy [16], and that there is a need to tackle the social and economic inequalities embedded in the current system in addition to environmental concerns. In the move from product to service models or where ownership is discouraged, for instance, an increasing volume of materials will become an asset class similar to money and property. This highlights the need for user protection and careful management of the transition, in order to prevent asset ownership being concentrated in the hands of a few[17]. Policy will therefore need to play a fundamental role in ensuring the move towards circularity also brings about a just transition[18].

Further resources and contacts

A brief overview of policymaking in the UK

A policy is a set of principles adopted to guide actions in pursuit of a goal, and often relates to a particular subject being developed by specific government departments in order to achieve their objectives. Legislation, by contrast, refers to law, which is enacted through Parliament and for which regulations provide detail as to how the legislation will be implemented, monitored and enforced. While policy must comply with existing law, it may also propose new laws as a way of enforcing actions that support all or part of a policy[19].

The formation of policy is not a linear operation and involves many actors that participate in processes of consultation, lobbying and calls for evidence, as well as the drafting of government manifestos and papers that set out the intended policy in a certain area. ‘Policymakers’ is a fairly loose term that can refer to ministers and their advisors as well as civil servants, scientific advisors, MPs and those working for wider government and public agencies. In the UK, citizens assemblies such as the Climate Assembly[20] are increasingly used at every level of governance to increase engagement and drive more citizen-centred policymaking[21], particularly when it comes to environmental matters; equally, the use of scientific research to develop evidence-based objectives has become more important[22], and was most recently highlighted at Cop26.

The levers which enable policy goals to be met can be divided into four main areas (see image above). These range from providing encouragement and guidance through to strict regulation, with policy making often using a combination of all approaches to drive each agenda.

References

[1]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/770709/DevolutionFactsheet.pdf

[2] (Gov.uk 2020) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/circular-economy-package-policy-statement/circular-economy-package-policy-statement

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-decarbonisation-strategy

[4] (EMF, 2021) Fix the economy to fix the climate

[5] (Naidoo et al, 2021)

[6] (Ghisellini et al, 2016); https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-on-applying-the-waste-hierarchy

[7] (Reike et al, 2017)

[8] (Kahupi, 2021)

[9] (Hartley et al, 2020)

[10] (Corvellec et al, 2021)

[11] (Tura et al, 2019)

[12] Kirsop-Taylor & Russel, 2022)

[13] https://ce-hub.org/nicer-programme/

[14] (WEF, 2021: Circular Trailblazers white paper)

[15] (Reike et al, 2017)

[16] (Corvellec et al, 2021)

[17] (Webster, 2021)

[18] https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/—emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_432859.pdf

[19] (BES, 2017) https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/An-introduction-to-policymaking-in-the-UK.pdf

[20] https://www.climateassembly.uk/

[21] (Wells et al 2021) https://link-springer-com.uoelibrary.idm.oclc.org/article/10.1007/s10584-021-03218-6

[22] (BES, 2017) https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/An-introduction-to-policymaking-in-the-UK.pdf

Demystifying Series: Policymaking and a circular economy

Share this article in downloadable PDF form

Open PDF >>