2002, McDonough & Braungart

Demystifying Series: Consumers, behaviour change and a circular economy

2022, CE-Hub Team

This paper is part of a series aimed at demystifying and providing context to a circular economy. The series is aimed at an audience of businesspeople, policymakers and others who may already have an understanding of the circular economy, are interested in implementing it in their field of influence and wish to know more. This Demystifying series addresses the ‘what’ of circular economy, and the upcoming What Works series will address the ‘how’. We recommend reading the introductory ‘Demystifying a circular economy’ paper in advance of this one.

Authors: Lucy Chamberlin & Georgie Hopkins

Reviewed by members of the Knowledge Hub Steering Group: Steve Evans, Simon Brown, Dan Dicker, Ali Moore, Isabelle Erixon, David Greenfield, Katie Lamb, Danielle Purkiss, Fiona Charnley.

What is consumption and why does it matter?

There are many different interpretations of consumption in academic literature and research. Some see it as the literal use or using up of material goods that are necessary for food, shelter or warmth, whilst others see it as a creative or symbolic activity that communicates identity, values and value to others in society. Paradoxically it can be viewed as the ultimate purpose of production and the duty of a responsible citizen, as well as a source of social inequality, waste and destruction[1]. Throughout the past 100 years there have been many critiques of consumption, both on grounds of human morality or social wellbeing and more latterly drawing attention to its impact on ecological systems. Increasingly, material consumption and affluence have been recognized as major drivers of environmental destruction[2], and the need to recreate economic systems that are aligned with the natural life support systems that people rely on has become correspondingly urgent.

Why are consumers important in a circular economy?

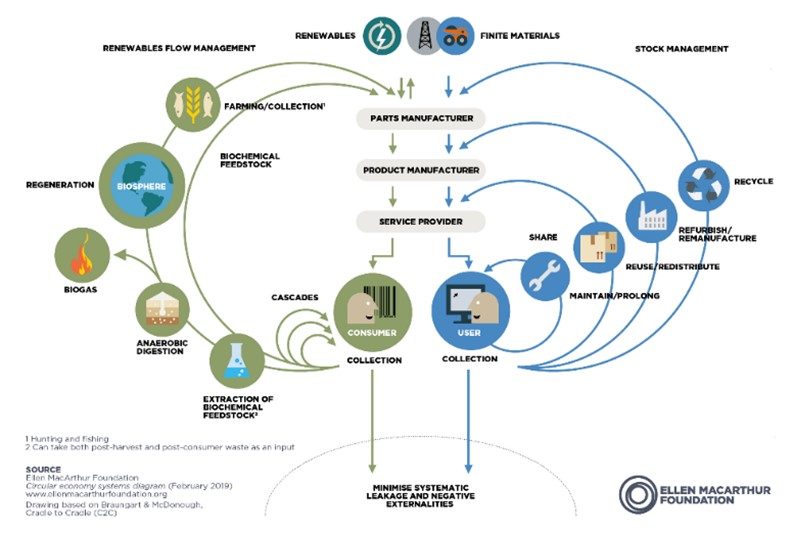

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s ‘butterfly diagram’ identifies the consumer and user as central to a circular economy

People have a vital role to play in any economy, particularly in their role as consumers or users of different products and services. It is consumers, after all, who to a large extent determine what and how something is purchased, how long it is used or kept, and when and how it is disposed of. Consumers can decide whether to buy something or to rent it, whether to throw it away or repair it, or to pass it on for reuse. Consumers are the shoppers, users, eaters, wearers and wasters of society – though of course, as well as free agents they may also be seen as victims of the production and marketing industries[3], influenced by corporate interests and bigger games of politics and power.

In spite of the critical role of consumers and consumption, most circular economy research tends to focus on technology, business models and material flows, and several authors have pointed to a lack of understanding when it comes to the part played by ordinary people in bringing about a change in systems[4]. Consumers have been called ‘the most central enabler of circular economy business models’[5] – yet consumers are not just passive automatons but also citizens, employees, family members and participants in society, and as such represent a complex and sometimes conflicting intersection of different wants, needs, activities and behaviours.

Changing consumer behaviour

Just as there are many different views of consumption within academic literature, so there are many different approaches to changing the behaviour of consumers, deciding whether it is necessary or ethical to do so, and the best ways of attempting it. Of course, advertising and marketing strategies like those employed by businesses for many decades to persuade people to buy things are one way of trying to change behaviour; other ways include the ‘push’ or ‘pull’ strategies employed by governments and local authorities, such as imposing or reducing taxes or fines, providing information, or changing the context in which people make decisions.

In the UK, the Government set up the Behavioural Insights Team, also known as the ‘Nudge’ Unit, back in 2010, and recently it has played a significant role in helping to craft communications that can influence people’s behaviour around the coronavirus pandemic[6]. In academia, the sub-field of Design for Behaviour Change has identified a spectrum that can be used to identify the type and persuasiveness of the behaviour change activity or messaging[7]. For example, a washing machine manual might inform a consumer about the eco setting they can use (informing), there might be incentives that encourage them to use it (encouraging), or the machine may be designed such that they are forced to use it (determining).

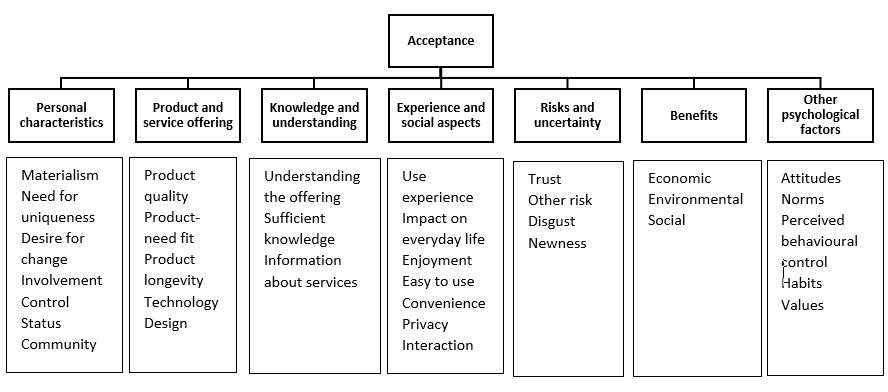

Diagram below: there are many different factors that influence consumers’ acceptance of a circular solution (adapted from Camacho Otero et al, 2018)

The factors, contexts and norms influencing behaviour change make it a very complex area to research. When it comes to circular economy, one study identified 34 different factors that can influence whether consumers are likely to accept the new ‘solutions’ or behaviours that might be required of them[8] (see figure 3 below). These include their own personal characteristics, the nature of the product or service on offer, whether they have enough of an understanding about it, social and experiential aspects like convenience and enjoyment, how risky it might be for them to adopt it, and any additional benefits it provides.

Why is behaviour change so difficult?

The concept of ‘sustainable consumption’ predates circular economy and has been a target of policymaking for some time[9], but in spite of this, habits and behaviours associated with sustainability or circularity have not necessarily become mainstream, and environmental impacts associated with consumption have risen significantly. Lots of different strategies have been used by policymakers and businesses to appeal to people to adopt more pro-environmental behaviours – for instance by recycling more or buying ethically sourced goods, and most of these rely on a perspective that puts the individual consumer at the heart of the changes[10], taking into account things like their values, attitudes and norms, and how likely they are to participate in a new behaviour. By engaging with the intrinsic values that people already hold, for instance, the values most closely associated with social and environmental sustainability can be strengthened or triggered[11].

However, there can be problems with a perspective that prioritises the individual consumer and their decision-making processes. For example, research in behavioural economics has shown that people are not always rational, self-interested economic actors that maximise their own advantages, but are largely influenced by assumptions and emotions and by others in their ‘tribe’ or echo chamber[12]. It is often presumed that people just need more information or education in order to act in the desired way, but information alone does not necessarily lead to action and thus techniques like ecolabelling have had only limited success[13]. In fact, people often intend to act in a way that benefits the environment, but in practice other priorities get in the way – and this has come to be known as the ‘values-action gap’[14]. Moreover, an individualistic perspective can place excessive blame on consumers and citizens – when wider infrastructures and systems might be what is really getting in the way[15]. People may be consuming to create an identity, to impress peers[16] – or simply during the process of feeding and warming themselves[17]. Environmental impacts are not always about conspicuous consumption, but often about what is normal and possible in a particular culture, community or infrastructure[18]. In the context of a circular economy, introducing new activities such as sharing, renting or repairing will be perceived differently by different consumers: for example, they may see them as more or less convenient or desirable, fitting with their identity (or not), or performed by other people in their social group (or not). The practice of sharing may have meanings of warmth and community for one group – and contamination or disgust for another!

How can consumers and citizens be engaged with a circular economy?

As well as context and culture, it is important to consider the ethical implications of trying to change other peoples’ behaviour: what gives one person or organization the right to try to influence others for instance? Even if it seems to be for altruistic reasons, behaviour change can often take an unhelpful and paternalistic approach in which one party assumes superiority over another. Nevertheless, in order to mitigate climate change and shift to a more circular economy, it is necessary for people, as consumers and citizens, to make some significant and imminent changes to their behaviour. Here are ten important points to remember when seeking to change behaviours towards a circular economy:

- What makes the new behaviour better?

Is the alternative really better than the status quo? Why? Sometimes it may appear more circular, e.g. in terms of waste reduction, but have unintended or negative consequences, e.g. in terms of health

- Be mindful of social norms

Who else is doing this? How is it currently perceived by media and society? Is it an ‘acceptable’ or even desirable practice in certain social groups?

- Show, don’t preach

People respond better to actions than words; if change and effectiveness can be demonstrated, others may join in

- Start from where people are at

It’s crucial to empathise with why people are not already engaged, to appreciate their current situation and dilemmas, and to show understanding before imposing change

- Convenience is king

If it’s not easy then it’s going to be difficult! People need ready alternatives that are going to fit in with their busy lives and multiple demands on their time

- Context is everything

It’s important to recognise that circular solutions that work in one scenario may not work in another, and what seems efficient may not always be effective!

- Don’t alienate people or make them feel bad

People don’t like to feel guilty – generally, they are trying their best in difficult situations and telling them they’ve got it wrong can just alienate them further

- Don’t just inform, encourage and narrate!

Facts and statistics may be accurate, but they are not always persuasive. Stories and incentives can be more effective when it comes to changing behaviours

- Language matters

The tide of greenwash is growing[19] and damaging genuine claims from sustainable products and services. Transparency and accuracy are vital to grow trust and adoption of circular solutions, and by keeping language simple a much wider audience can be engaged.

- Keep it simple and make it fun!

People don’t like being bombarded with complex information. Focus on one behaviour at a time, one audience at a time, and make it fun – or at least more attractive than the alternative!

Organisations working on behaviour change for circularity or sustainability

Just a few of the organisations that have done research on behaviour change and who work on engaging people with more sustainable or circular ways of consuming and living:

WRAP: the Waste and Resources Action Programme, which works with government, businesses and society to provide evidence and increase action around waste reduction and sustainability.

PIRC: the Public Interest Research Centre has done a lot of work around how narratives, frames and communication can influence action; see for example their Common Cause Handbook.

UCL Centre for Behaviour Change: UCL’s Centre for Behaviour Change provides cutting-edge research on the science and practice of behaviour change in social and environmental fields.

The Behavioural Insights Team: the so-called ‘Nudge Unit’ works in collaboration with governments, businesses and charities to inform policy, create interventions and improve public services.

ReLondon: a partnership of London’s boroughs that works to reduce waste in the capital and increase transition to circular economy.

References

[1] Kjellberg, 2008; Bourdieu, 1984; Gabriel & Lang, 2006; Warde, 2014; Belk, 1988

[2] Ivanova et al., 2015; The Royal Society, 2012; Thøgersen, 2014; Wiedmann et al., 2020

[3] Gabriel & Lang, 2006

[4] Camacho-Otero et al., 2018; Piscicelli & Ludden, 2016; Chamberlin 2021

[5] Kirchherr et al., 2017, p. 228

[6] https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/nudge-unit; https://www.bi.team/

[7] Lilley & Wilson, 2017; Chamberlin, 2021

[8] Camacho Otero et al., 2018

[9] UNEP, Middlemiss, 2018.

[10] Jackson, 2005b; Klöckner, 2015a; Shove, 2010; Thøgersen, 2014

[11] Public Interest Research Centre, 2011; Schwartz, 1992

[12] Kahneman, 2012; Kahan, 2017

[13] Dangelico & Vocalelli, 2017; Ford & Norgaard, 2018; Marshall, 2018; Middlemiss, 2018

[14] O’Rourke & Lollo, 2015

[15] Kjellberg, 2008

[16] Baudrillard, 1998; Gabriel & Lang, 2006; Julier, 2014; Belk, 1988

[17] Warde, 2014; Shove & Warde, 2002

[18] Shove & Warde, 2002, p. 12

[19] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/global-sweep-finds-40-of-firms-green-claims-could-be-misleading

Demystifying Series: Consumers, behaviour change and a circular economy

Share this article in downloadable PDF form

Open PDF >>